Ladislav Hanka was born in America, the son of Czechoslovakian immigrants. If his parents seem to have emerged from another time, it’s because they did; while automobiles were not unknown in Czechoslovakia, only the rich owned them. Most people rode horse-drawn buggies.

Hanka’s father studied medicine until 1939, when the Nazis closed Czech universities. He resisted; he survived. After the war, on March 29th, 1948, he married a young woman named Eva. The allies pulled up stakes, leaving the country to its own devices and to the appetite of the Soviet Union. In 1950, the couple fled. The money they’d managed to scrimp together was lost. They made their way through forests and bogs, careful not to be seen by police, military patrols, or smugglers; in time, they made their way to Germany, and to America, where they would find peace and meaning, and where they would raise their children.

Ladislav, their boy: he would be an artist, his mother was sure. It was his destiny.

“I just drew ceaselessly,” Hanka told Revue. Compliments from older people proved more frustrating than flattering: couldn’t they see that his art didn’t look the way it was supposed to? “Rembrandt did it right. I didn’t.”

Learning to do it right takes time. It takes ten thousand hours, in fact; at least, it does according to researcher Anders Ericsson. Hanka finds the idea convincing. “There’s something to that. Hand a guitar or a violin to a kid, and for two years they’ll make squeaky, awful noises. A few years later, they aren’t sounding too bad. And in time they make it their own.”

He wandered the beautiful forests and trout-filled rivers of West Michigan. He drank from streams. He took in the vibrancy of young trees and the depth of fully ensouled older trees. Nature was both peaceful and inspiring. It wasn’t something separate. “We are nature,” he said.

When it was time for college, he studied biology and zoology, partly for practical reasons—he would need to make money, as his father reminded him—but also because he had a great affection for the creatures of the world. The studies gave him insight into anatomy, into underlying structures, something critical to drawing well. “That was very important. The point isn’t to make it super-realistic but to be enough of an expert to make it believable. You can stylize from there, but you need the understanding first.”

He continued to learn. In time, he went back to art school, where he was shown “a lot of academic art that no one likes. I succeeded in un-learning quite a bit.” (Think you’ve learned your mother’s face? Try drawing a three-quarter profile of her from memory. Seeing is something you learn to do).

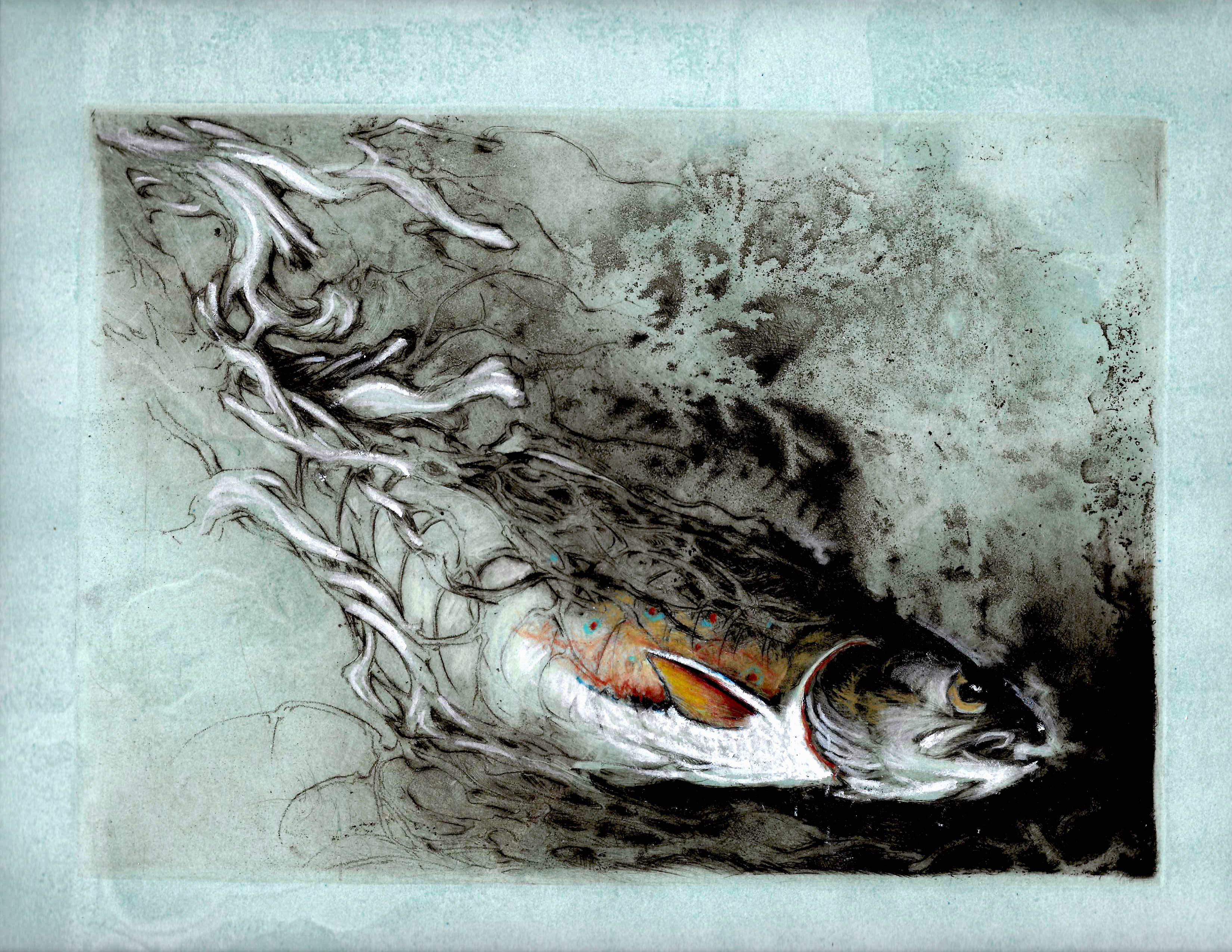

He got good. His work, often focusing on birds, fish, trees, landscapes, and people, is remarkable: technically accomplished, it has at times a haunting, nostalgic quality, as if the subjects were seen once and recalled years later.

Sometimes, that’s literally true. He was ten years old when, while on a fishing trip with his father, he met an old black man. The man had been born a slave, he said; he had been three years old when the Emancipation Proclamation took effect. He looked stunningly old. Writing about the encounter decades later, Hanka drew the man from memory. He was startled to discover how well he remembered the man. “It was him. It was really him.”

At times, he will sit with his sketchbook on his knee and draw a tree. “I stare. Trees have pulses; there’s a contraction and an expansion. It’s clear that this is a living creature.” There are trees in Michigan that existed long before Europeans came to the continent (in Fayette, MI are trees estimated to be 1400 years old). In talking with him, you come to understand that Hanka feels honored to capture something of their spirit.

Nature collaborates. In 2014, he contributed to ArtPrize The Great Wall of Bees. In a locked cabinet, 5,000 bees made honeycombs on prints he’d created, introducing a layer of randomness (or seeming randomness). This both deepened the natural themes of his art and made the case that bees are extraordinary, that they matter.

He avoids digital techniques, prefers methods that are either by hand or as close to being by hand as possible. In galleries, he finds himself walking by digital content. “Photographs are kind of bankrupt,” he said, even if some photographers are great. He wants the real thing. He isn’t a Luddite; he has a website and an email address, for instance. Then again, he still uses a rotary phone.

When he teaches, he finds himself telling students to worry less about making money than making something meaningful. “You don’t need a lot of the things they say you need.” He isn’t opposed to commercial art—the drawing of a trout on every bottle of Bell’s Two-Hearted Ale is his—but he thinks most people can get by on less than they think. Beans aren’t expensive, and, besides, they’re probably better for you than most restaurant meals.

He marvels at what other artists have accomplished over the centuries. “I find myself interested in those that leave an impression that goes really deep,” he said. “Rembrandt, Da Vinci, Whistler.” His art makes deep impressions, too. Like the heartbeats of trees, those impressions are available to anyone willing to slow down and look. There. See?

Find Hankaís work and more at ladislavhanka.com.