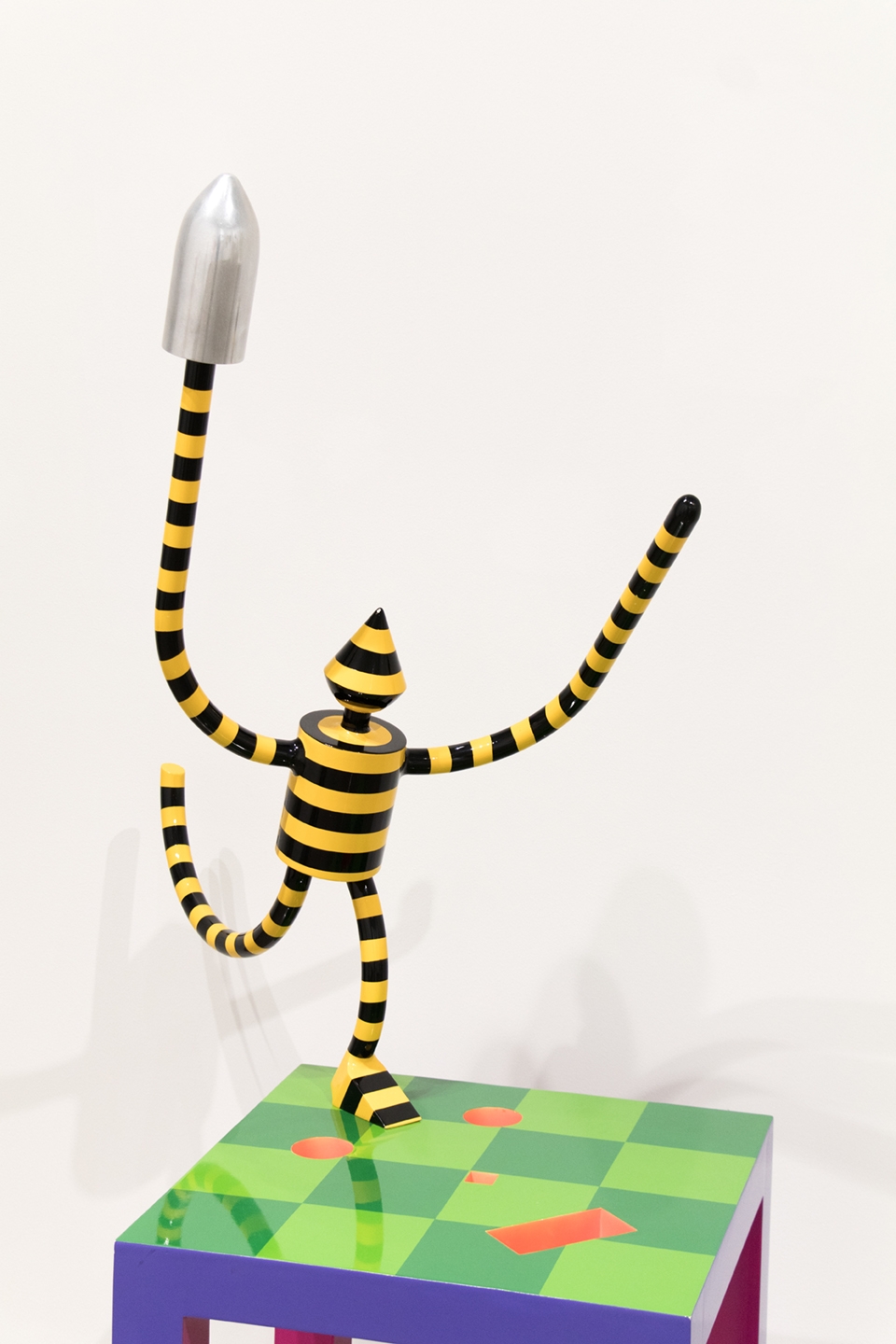

Popeye, boxing gloves, skulls, speaker cones, even UFOs — references to events and symbols from 20th century popular culture permeate the work of the late Billy Mayer, a well-known and well-liked Hope College art professor.

Mayer, inspired by memories of his childhood and personal interests, also tackled progressive and political themes, ranging from guns and violence to the decline of the manufacturing economy to issues of environmental degradation and consumerism.

A contemporary and visionary in a socially conservative community, Mayer left a lasting mark through his artwork and his impact on students. The professor of sculpture and ceramics died suddenly in November 2017 at age 64, and it sent shockwaves throughout the campus and community.

A special exhibit at Hope College’s Kruizenga Art Museum, In Memory: The Art of Billy Mayer, offers a retrospective look at his artistic career.

“This is a rare opportunity to see a fairly comprehensive sweep of it,” said Charles Mason, curator and director of Kruizenga Art Museum. “Most of his artwork is in private collections. There won’t be another chance to see a group of his artwork like this for a long time.”

Culled from Mayer’s private collection, the exhibit includes a broad range of his work on loan from his estate. The show features metal and mixed-media sculptures, collages, photographs and more.

All of the works are for sale and can be bid on through silent auction, which runs in conjunction with the exhibition and concludes on Sept. 8. Proceeds support an endowed scholarship in Mayer’s name to benefit future generations of Hope College art students.

With the help of Mayer’s widow and friends, Mason had access to his house and studio and works that were packed away. The show is meant to be a survey and includes work from the 1980s through 2017.

Though Mayer taught ceramics and worked heavily with functional pottery, Mason wants to show a different side of the artist. Mason said he was surprised to uncover Mayer’s photography and gathered work that examines the theme of memory, as well as reflects who he was as a person and artist.

“For me, I had lots of conversations with him over the last five years, and what strikes me is how much his personality comes out in his artwork,” he said. “He had a very dry sense of humor. His artwork truly is a manifestation of his personality.”

Some pieces are overtly humorous, while others have a darker edge. There are certain themes that come up again and again related to the environment, social identity, cultural values, and the American consumer culture, which he found problematic, Mason said.

The artworks have a personal connection to Mayer’s life, but he also “intended for his work to evoke memories in others, encouraging all to find their own meanings in his art” and inspire contemplation and social consciousness.

“He hated the word ‘whimsical,’ but his works are playful for sure,” Mason said. “At first glance, they seem quite cheerful and charming and playful, but … he’s really dealing with pretty serious issues. It’s that multilayered nature of his work that I think is really fascinating.”

A native of Minnesota, Mayer began young by making his own sculptures working at his father’s workbench in the basement, which ignited a passion and drive that kept him up at night and led him to study art in college.

He graduated with a bachelor of fine arts from the University of Minnesota and a master of fine arts from Pennsylvania State University in 1978, then moved to Holland to join the faculty of Hope College where he worked for nearly 40 years.

Along with teaching, inspiring and mentoring countless students, Mayer continued to show his artwork in both solo and group exhibitions at museums and galleries throughout the Midwest.

Mayer was very involved in planning for the Kruizenga Museum, which opened in 2015, and was good friends with lead donors and Hope alumni Richard and Margaret Kruizenga, Mason said.

In Holland, Mayer’s legacy lives on through several public sculptures, including Sun Dog II outside Phelps Hall on the Hope College campus, Perro del Sol V outside the Herrick District Library in Holland, Midwinter Horn in the Nyenhuis Sculpture Garden on the Hope College campus, and Smokestack Lightning at the Midtown Center in Holland.

Those public sculptures sparked conversation and criticism in the larger community and gave him a bit of notoriety. Good or bad, he liked the idea that people were talking about his art, Mason said.

“The one in front of the Herrick District Library generated a lot of discussion,” Mason said. “Some people really liked it, some people really didn’t like it.”

Installed in 1982, the library sculpture is geometric, painted with bright colors, and its form and color appear to change as you move by it depending on the angle, Mason said. Much like Mayer himself, it was “just so totally not like anything else that existed in Holland.”

In Memory: The Art of Billy Mayer

Kruizenga Art Museum, Hope College

271 Columbia Ave., Holland

Through Sept. 8

hope.edu/arts/kam, (616) 395-6400