Beneath the stained drop ceiling of the American Postal Workers Union West Michigan Local on a recent March evening, Kent County Democrats were strategizing on how to build off a solid performance in November 2018.

President Donald Trump would rally in Grand Rapids in 15 days, while several Democratic hopefuls would swing through Southeast Michigan within the week.

It was a few days before St. Patrick’s Day, and the 2020 election was gaining steam. But in traditionally and oft-perceived conservative West Michigan, it’s tough not to sense additional momentum favoring Democrats.

They’re coming off a 2018 election in which:

- Gov. Gretchen Whitmer took 17 of 83 counties in the state, including winning by more than 11,000 votes in Kent County, which hadn’t voted for a Democratic governor for at least two decades.

- Democrats picked up two seats on the Kent County Board of Commissioners, flipping one to Democrats in northeastern Grand Rapids and picking up a vacant seat in Kentwood/Wyoming by 1,200 votes.

- State Sen. Winnie Brinks flipped the 29th Senate district for Democrats over former state Rep. Chris Afendoulis, a district considered gerrymandered to favor Republicans.

Apart from recent success, though, is what lies ahead. The population of Grand Rapids is growing and trending younger, with presumably more progressive voters. Outside the city, pundits point to metro areas like Rockford, Walker, Wyoming and Kentwood for turning out Democrats in 2018. It builds off Democratic bases in Muskegon and Kalamazoo.

Demographic shifts could have major implications as new state legislative and congressional districts are drawn based on 2020 Census data. At the same time, Michigan will have a new process for drawing these districts after the broad support for Proposal 2 in 2018, which created an independent commission to draw districts instead of the politically motivated process open to gerrymandering by both Republicans and Democrats.

“You definitely see it’s becoming more fertile ground for Democratic candidates,” Dennis Darnoi, a GOP strategist, said of West Michigan.

Reaction to 2016

The Kent County Dems’ March meeting was an early glimpse of the party’s strategy for 2020. It was led by two volunteers spurred to action, like many in the area, after President Trump’s election in 2016.

That included Kim Gates, the precinct organizing chairperson, and Kent County Democrats chairperson Gary Stark, both relative newcomers on the scene.

Gates said the plan is to target and build support in all 252 precincts in Kent County with district organizers, which are not the same as precinct delegates. Organizer training is scheduled to start in June. The plan is known as the “First Steps to 2020.”

“We have a lot of delegates,” Gates said. “We don’t have a lot of organizers.”

The statewide Michigan Democratic Party also has taken notice of West Michigan. Chairperson Lavora Barnes says a three-person field staff was added to West Michigan in 2017, and will remain through 2020.

“We’re going to grow that team of field organizers. We’re not conceding any part of the state,” Barnes said.

The Democratic National Committee also is providing funding for a 2020 Organizing Corps, which includes a $4,000 stipend geared toward college juniors.

Barnes, who was elected to lead Michigan Democrats earlier this year, said she “spent a lot of time” in West Michigan while running for chair.

“After what happened in 2016, folks woke up the day after the election ready to fight back and win,” she said. “There’s serious evidence of excitement.”

Stark, who was elected Kent County chair in December, said that was basically his path to leadership within the party. He’s a retired university professor and dean, spending more than 40 years in higher education.

“I retired in 2015. Then 2016 happened,” Stark said. “As with many people, I got energized and activated and became much more involved in local and national politics.”

Changing demographics

While Democrats may be publicly optimistic and self-promoting, a key question remains: Will that optimism actually lead to a gain in seats in 2020 and beyond? Several factors are at play.

While anti-Trump sentiment appears to remain strong among Democrats and moderates, it’s unclear who will be the party’s presidential nominee to face off against a presumptive Trump re-election campaign. It’s also unclear who will be recruited to run in the 2nd, 3rd and 6th congressional districts, seats now held by Republicans Bill Huizenga, Justin Amash and Fred Upton, respectively.

Huizenga and Amash easily fended off their challengers in 2018, each garnering about 55 percent of the vote. Upton’s race was the closest after beating Matt Longjohn 50-46 percent, or by about 13,000 votes.

The 2nd and 3rd congressional districts are often cited as prime examples of Republican gerrymandering. The 2nd spans from Ludington to Holland along Lake Michigan and inland to Wyoming. Amash has reportedly raised concerns about the way his district was drawn in 2010 in a way that also helped U.S. Rep. Tim Walberg, R-Tipton, in the 7th congressional district.

The Detroit News reported emails that surfaced in February during a lawsuit against gerrymandering suggested Amash’s district was drawn in a way that benefits the Republican Walberg while not diluting Amash’s GOP voters too much.

Aside from the candidates, though, Darnoi sees momentum shifting for Democrats based on demographics. The population is growing around the state’s two biggest cities, Grand Rapids and Detroit, while it’s shrinking or remaining stagnant in Republican-held areas to the north.

When redistricting happens, “You’re going to have to be drawing some of those northern districts a little farther south to gain population to meet requirements,” Darnoi said. “That’s going to create more diverse districts in the southern portion of the state. … That should give Democratic candidates an advantage.”

For West Michigan, Darnoi says it will still depend on which candidates are running. He pointed to Kent County in 2018, where Whitmer beat GOP challenger Bill Schuette by 11,600 votes and Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson beat Mary Treder Lang by 7,500 votes. Attorney General Dana Nessel, meanwhile, lost Kent County to Tom Leonard by 10,000 votes.

“(Nessel) wasn’t the type of candidate that could be fully embraced by Kent County,” Darnoi said, referring to Nessel’s outspoken “further left” politics. Trump won Kent County in 2016 by 9,500 votes.

“Depending on who the candidate is in 2020, it could again be a battleground area in the presidential election,” Darnoi said. “(Kent County) hasn’t completely flipped to being a Democratic area yet.”

A representative for the Kent County GOP was unavailable for comment.

Ironically, some observers believe Republican mega-donors like the DeVos family are helping drive the demographic changes that are bringing younger, more progressive voters to West Michigan.

Ed Kettle, a longtime Democratic consultant in Grand Rapids, has watched cities in West Michigan grow increasingly progressive in recent years.

“Oddly enough, it was the wealthy people, mostly conservative money pouring in for development projects,” he said. “Those bring in people, and those people are either apolitical or tend to be a little more progressive. I’ve seen these demographics shift before, but this is the largest based on pure population growth.”

“Absolutely,” Darnoi agreed. “The investment in Grand Rapids as well as Detroit make it a desirable place for younger individuals to want to work. The more attractive a city is, the more likely you are to bring in younger voters, who tend to be more aligned with Democratic orthodoxies.”

However, Kettle says the rural and agricultural areas of West Michigan will continue to be a challenge for Democrats. He thinks candidates should be targeting these voters, the way U.S. Sen. Debbie Stabenow has over the years as a champion for the Farm Bill.

“It’s really Democrats who have been taking care of farmers,” Kettle said. “I get it — guns and babies — but your economy is collapsing because this guy (Trump) wants his tariffs.”

David Doyle, another longtime Democratic consultant in Grand Rapids with a deep knowledge of political history, noted former Congressman Richard Vander Veen was the last Democrat Grand Rapids sent to Washington. The vote in 1974 was a referendum on President Richard Nixon; Vander Veen lost his seat to Republican Harold Sawyer in 1976.

“There hasn’t been a Democrat elected (to Congress) since in this part of the state,” Doyle said. “That’s truly because Republicans and Democrats cut districts at the state level and congressional (races). Democrats always sided with Detroit — ‘We’ll give Detroit their Democrats, but we’re going to have Republicans on the west side of the state.’”

Gerrymandering no more?

The anticipation of new 2020 Census data will give way to Michigan’s new redistricting process after the approval of Proposal 2, a constitutional amendment Michigan voters passed to create an Independent Citizens Redistricting Commission to draw new districts. The 13-member commission is made up of randomly selected voters through an application process (four Democrats, four Republicans and five unaffiliated with those parties) and will draw new maps for the 2022 election. Previously, the Legislature and the governor decided new districts based on new Census data every 10 years.

Some districts could also be redrawn for the 2020 election based on the outcome of a lawsuit brought by the League of Women Voters. As of mid-March, a three-judge panel was still weighing a decision on the case claiming Michigan Republicans unfairly drew districts to hurt Democrats. The outcome could cause some new districts to be drawn for 2020.

“We’re excited to fight on a fair playing field,” said Barnes, the chair of the Michigan Democrats, adding that — at this point — it’s hard to even guess what the new 2022 districts will look like. “I do know that it will be more fair than now.”

Indeed, the point of independent, non-partisan redistricting is not to favor one party over another, but to make races more competitive.

“By all accounts, it should be fairer, more even-handed and less partisan than it has in the past,” said Stark, the chair of the Kent County Democrats. “I think we’ll see much closer elections and perhaps an upsurge in Democratic seats.”

Kettle agrees the new redistricting process “will hold well for us. This is becoming a more progressive side of the state. The grand mystique of the Republican Party in Michigan might be dinged a little bit.”

Even without new Census data, GOP strategist Darnoi imagines new district lines in West Michigan congressional districts based on population shifts could benefit Democrats. He said the 2nd district could include parts of Kalamazoo, Portage and Grand Rapids.

“Between the 3rd and 6th, they could come up with what would be a really good Democratic-leaning district,” he added. “When you’re talking about demographic changes heading into redistricting, there is potential to see a district with a Democratic congressman from the west side.”

The same goes for state House seats drawn based on new populations, he said.

“I think starting in the 2022 cycle, you’re going to have very competitive seats on the west side. They’ll be considered toss-ups, battlegrounds,” Darnoi said. “It’s just how our population is going and where we’re growing.”

So what does this mean for Michigan Republicans, who handed Trump 16 Electoral College votes in 2016?

“In order for the GOP in Grand Rapids, Kent County and across Michigan to be successful, I think it needs to focus more on the economic quality of life and less on social issues,” Darnoi said.

Problem is, that focus on social issues — or appealing to the base — may get Republican candidates through a primary, but not a general election.

“Unfortunately now where the GOP base is, if you want to be a successful candidate, those are the issues the base is looking to hear about,” Darnoi said. “We do have this quandary: You can win a primary by appealing to base issues, but then you’ll really struggle to connect with independents, conservatives, as well as Democrats.

“You have to be striking that balance with more pragmatic governing. It’s going to be very difficult to do in 2020 as long as Trump is the nominee. The party is going to serve as an echo chamber for whatever Trump is talking about in this election. I don’t know how anyone could legitimately say that what we saw in 2018 wasn’t part of a repudiation of the Trump message.”

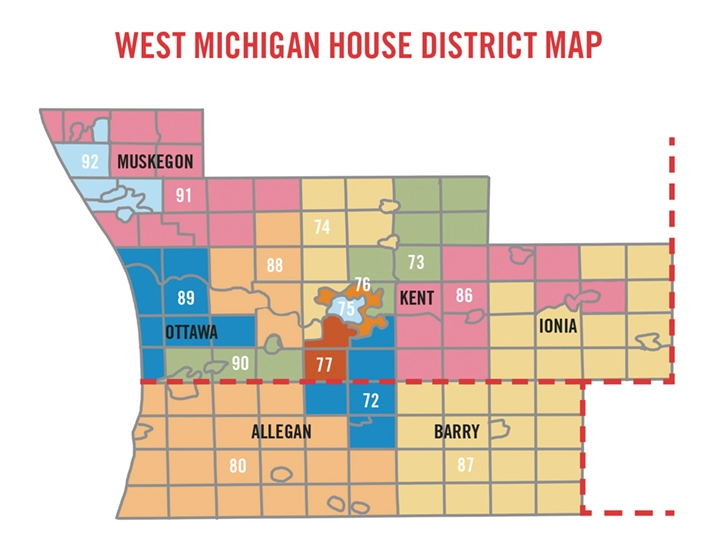

While Democrats are stepping up their organizing, state chair Barnes said “there’s always been interest” from the party in West Michigan. For example, former state Rep. Brandon Dillon wasn’t expected to win the 75th district in 2010. After the election, his district was drawn to favor Democrats even more to help Republicans elsewhere in a process known as “packing and cracking.” (Dillon, of Grand Rapids, went on to chair the Michigan Democratic Party from 2015 through 2018.)

“The difference now is we are truly organizing on a grassroots level all over the state,” Barnes said. “It’s just all hands on deck.”